Encouraging the use of evolutionary biology concepts and ecosystem protection to mitigate climate change causes and consequences in agriculture.

Publié le 4 novembre 2022 – Mis à jour le 4 novembre 2022

Author

Etienne Danchina

a Université Côte d'Azur, INRAE, CNRS, Institut Sophia Agrobiotech, Sophia Antipolis, France

Introduction

I wrote this advocacy both as a citizen of a world changing due to climate change and biodiversity loss, and as a scientist whose research has the potential to inform translational scientists and policy makers and lead to innovations that may eventual contribute to the mitigation of climate change and its consequences.

Two main parameters directly influence climate change caused by human beings: (i) the individual impact of each citizen due to their behaviour and consumption habits, multiplied by (ii) the number of individuals on earth.

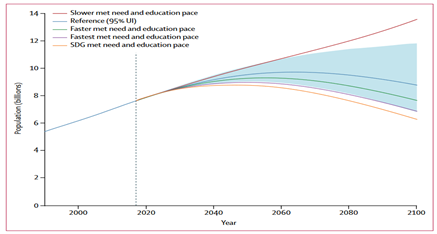

Concerning the evolution of the global human population, a recent study combining multiple scenarios forecasted a likely peak at 9.73 billion people (8.8-10.9 uncertainty interval) around 2064 (Figure 1) followed by a decrease to 8.8 billion in 2100 (6.83-11.8 uncertainty interval)1. This means the youth of the current generation and the next will experience the highest population levels on Earth. A peak of population translates into a peak of demand for energy, food, feed, housing, equipment, etc. putting our planet under high pressure. Although further investment in female education and access to contraception can hasten declines in fertility and slow population growth, the trend remains a growth with a peak in the next 40-45 years.

Figure 1. Global population forecast in the reference, slower, faster, fastest, and sustainable development goal (SDG) pace scenarios, 1990–2100 according to ref.1; UI= uncertainty interval.

I. Advocacy as a citizen of a changing world

With this parameter of population and the associated growth in demands in mind, and regardless of the expected accompanying scientific discoveries and technological progress, collective efforts must be made to decrease individuals’ environmental impact through changes in habits and behaviours. The successive reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) provide clear guidelines to achieve the behavioural changes necessary to reduce human-induced greenhouse gas, a cause of climate change. However, for the population to adhere to these measures, governments and institutions must adopt irreproachable and exemplary behaviours themselves. Recently, several severe ecological nonsenses like the organisation of the FIFA World Cup in Qatar with air-conditioned open-air stadiums or the organisation of the Asian winter Olympics in the middle of the Saudi Arabian desert yield a doubly detrimental effect. First, directly as a major source of ecosystem degradation and greenhouse gas emissions, and second, these terrible examples have disastrous effects on the acceptance by populations of measures to reduce their own individual environmental impacts. These inconsistencies jeopardise a large part of the efforts spent to try to change people’s behaviour and the lack of condemnation by the international community is as incomprehensible as the decision to award these events in these conditions. Although the previous generation was not sufficiently informed about the ecological consequences of their decisions and acts, there is no excuse for the current generation that knows and is widely informed but decides to ignore the consequences. This is especially true for this segment of the population which govern states, institutions or big companies and generally has a high education level. In my opinion, these nonsenses are still possible because of a feeling of total impunity. This should absolutely change, and international rules and regulations should rapidly incorporate the notion of “ecocide” at different levels up to the level of “crime against the planet”, for the most terrible cases, inspired by the notion of crime against humanity. This idea of a law of ecocide has already been proposed multiple times with clear arguments and common sense, but never yet adopted 2,3. Definitely, ecocides not only have a direct negative impact on ecosystems but a longer-term negative impact on the well-being and health of whole communities and populations, even threatening their survival. These ‘crimes against the planet’ should be more unanimously condemned and the informed persons responsible for these decisions should risk prosecution, prison, and fines high enough to be dissuasive. The money generated by these fines could in turn be used to support actions against climate change, including improvement of scientific education worldwide.II. Advocacy as a research scientist working on plant health

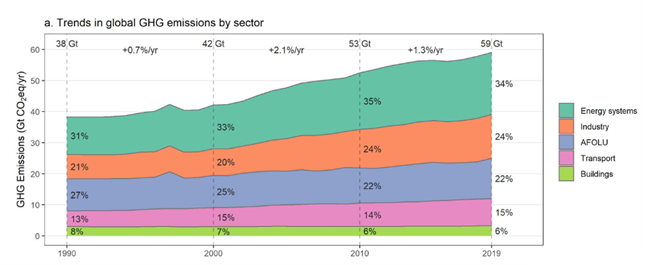

According to the 6th and latest IPCC assessment report (Chapter 2 of Working Group III), agricultural, forestry and other land use are collectively responsible for approximately 22% of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions worldwide (Figure 2). This assessment has been rated as ‘robust evidence – high agreement’ and places agriculture and other human-modified land usage as the third source of greenhouse gas emission globally after energy systems and industry, albeit with wide regional differences. In the agricultural sector, land use and land conversion alone are the main contributors to greenhouse gas emissions (51%). Logically, according to the IPCC report (Chapter 7 of Working Group III) the primary means of mitigation, with the single largest potential to reduce emissions, is the protection of ecosystems (forests, wetlands, savannas, and grasslands).

Figure 2 Total annual anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions by major economic sector.

(GHG= greenhouse gas, AFOLU= agricultural, forestry and other land use).

As noted in the introduction, the global population is growing. In addition, the diet is changing in developing countries. These two parameters will increase the global food demand and put even higher pressure on the agricultural sector. To meet the corresponding crop demand, an increase of 25-70% above current production levels will be necessary4. This cannot be at the cost of expanding cultured land surface as land usage and conversion is the main source of greenhouse gas emission in agriculture. Hence, the yield per surface must be improved. However, this also cannot be achieved by applying more synthetic fertilisers and pesticides, because the first is a known source of N2O greenhouse gas and the latter negatively impacts biodiversity and pollutes water and soils. In addition to progress in crop variety selection and wider usage of agroecology, more durable alternatives to currently used fertilisers and pesticides must be found. A study of five major crops that sustain the lives of billions of people (wheat, rice, maize, potato, and soybean) has shown that pests and parasites are responsible for average annual yield losses of 17.2-30.0%, depending on the crop5. And this is despite the considerable efforts already deployed to control them. Furthermore, climate change has been associated with reduced efficacy of pesticides6 and the expansion of pest and parasite distributions poleward7. Hence, agriculture is both a cause and a victim of climate change.As an evolutionary biologist working for France’s National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment (INRAE), I hope my research can contribute, even modestly, to the mitigation of climate change and biodiversity loss. My main goal is to understand how pests and parasites have evolved the ability to manipulate their hosts and how these species adapt to environmental changes including host defence systems and methods deployed to control them. I am convinced that better understanding how these species evolve and adapt will foster development of more environmentally sound, durable, and efficient solutions to reduce the damage caused by pests and parasites to agriculture. To investigate these questions, I use comparative and evolutionary genomics and bioinformatics, including artificial intelligence in collaboration with Université Côte d’Azur. Despite its high potential, evolution and its concepts have not yet fully benefited all fields of biological research and their applications8. I advocate a broader adoption of evolutionary biology concepts in research, including applications in the development of new control methods against agricultural pests as well as evolutionarily informed policy decisions for biodiversity protection and ecosystem preservation.

Concluding remarks

As seen in section II, protection of ecosystems is the primary means of mitigating greenhouse gas emissions in the agricultural sector, a sector under high pressure due to global population growth. This protection of ecosystems needs collective efforts and can only be realised if appropriate rules and regulations are applied. This can be achieved by enforcing ecosystem protection means, including laws allowing trials for ecocide or crimes against the planet as proposed in section I. As pest and parasites generally evolve faster and are more rapidly adapted to climate change than the hosts we want to protect, I also advocate a wider adoption of evolutionary biology concepts to help and guide development of more efficient means of mitigation.Bibliography

- Vollset, S. E. et al. Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet 0, (2020).

- Polly, H. Eradicating Ecocide: Exposing the Corporate and Political Practices Destroying the Planet and Proposing the Laws to Eradicate Ecocide. (Shepard-Walwyn (IPG), 2016).

- Higgins, P., Short, D. & South, N. Protecting the planet: a proposal for a law of ecocide. Crime Law Soc Change 59, 251–266 (2013).

- Hunter, M. C., Smith, R. G., Schipanski, M. E., Atwood, L. W. & Mortensen, D. A. Agriculture in 2050: Recalibrating Targets for Sustainable Intensification. BioScience 67, 386–391 (2017).

- Savary, S. et al. The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nat Ecol Evol 3, 430–439 (2019).

- Matzrafi, M. Climate change exacerbates pest damage through reduced pesticide efficacy. Pest Management Science 75, 9–13 (2019).

- Bebber, D. P., Ramotowski, M. A. T. & Gurr, S. J. Crop pests and pathogens move polewards in a warming world. Nature Clim. Change advance online publication, (2013).

- Carroll, S. P. et al. Applying evolutionary biology to address global challenges. Science 346, 1245993 (2014).